Parachutist General Giuseppe Palumbo: THE FOLGORE MAN

East Africa, 1942, Colonel Cinelli to Lieutenant Palumbo: "In Africa there are still no asylums, your idea is crazy."

That crazy idea will allow Lieutenant Palumbo to personally lower the British flag and take Harrington's fort. We dedicate an entire section to this man. Parachutist General Giuseppe Palumbo was no ordinary man. He was the bridge between the past and the present. Already in himself a Paratrooper is not just any man.

Let alone a Paratrooper who conquers an unassailable fortress, is captured and escapes (13 times!) from ironclad British prisons, travels 8.000 km on foot, swims seven hours in the ocean with a dagger in his teeth, slaps a journalist who insults his Paratroopers, returns the medals for valour to the President of the Republic, the latter guilty of having rewarded the first person responsible for the massacre of the Ardeatine trenches, jumps into TCL from over 4000 thousand metres at over eighty years of age.

A man, therefore, who represented the absolute embodiment of the Paratrooper, as well as the Commander and the hard and pure Fighter with a courage bordering on the unbelievable (often even beyond this limit...).

He is MAN FOLGORE for all intents and purposes, no buts or buts.

An example therefore, a beacon, for his subordinates and for all Paratroopers who have had the honour to serve under his command.

A pride for your Commanders and not only (the Honourable Giulio Andreotti will hail your reckless behaviour...)

An officer born in 1915, the son of a cavalry officer, Giuseppe Palumbo took the officer trainee course in 1936 and two years later left for East Africa, participating with the 2nd Colonial Battalion in the rounds of war operations in the territory of the Gallo government.

The then Lieutenant Palumbo was the protagonist of legendary manoeuvres at the command of indigenous bands. The most sensational was the capture of the British fort of Harrington after six days of furious fighting.

This is how he recounts that experience:

"Before the fort could be taken, the resistance of Dirsale, a small village at the foot of Harrington, had to be crushed.

While the various battalions went on the assault, I was in reserve with my men. Tired of this nerve-wracking wait, I went to the Attack Command, to Colonel Cicinelli, and volunteered to occupy the village with my band. The Colonel tells me, laughing, that there were no asylums in Africa yet, making me realise that my proposal was crazy.

However, he gives me the go-ahead and I play the card of surprise and psychology: at night, after a day of intense fighting, the exhausted soldiers logically feel a drop in tension. I take advantage of this situation and, with a few men, launch a very violent attack in the middle of the night with deadly hand grenades.

The surprise works, the defenders of Dirsale abandon the village and seek refuge in the nearby fort of Harrington'.

The first objective is achieved, now the most arduous task remains. Palumbo and his men remained bottled up in the front line 'rejecting repeated enemy counter-attacks' - as stated in the justification for Palumbo's promotion to S.P.E. for war merits precisely because of that feat - and holding their ground for three consecutive days despite furious enemy bombardment from both the ground and the air.

Finally, on the fourth day, having received the order to storm the blockhouse some fifty metres away, we launched hand grenades, putting the last remaining defenders to flight, capturing weapons and ammunition'.

"Of course, the fort did not fall only because of my assault but all the other battalions engaged in the attack - Palumbo points out - I, however, had the great satisfaction of going in first and personally lowering the British flag that the fleeing defenders did not have time to save.

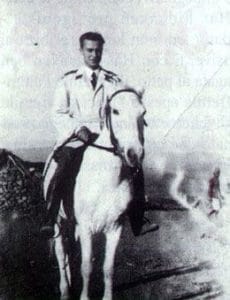

As his personal 'booty' from the war, Palumbo took a splendid white horse (horse-riding had always been a great passion of his, passed on to him by his father, a cavalry officer). Riding that steed, he was hailed as a triumphant hero by his ascendants, who were astonished by the courage he had displayed in conquering the fort.

The African campaign, unfortunately, did not only record successes: after so many daring exploits, the days of bitterness arrived. Having taken his unit prisoner, Palumbo with a handful of men attempted to reach the Amba Alagi where the Duke of Aosta was still fighting. Surrounded by overwhelming troops, he was forced to surrender in the Sorfella plain after a bitter fight.

He escaped almost immediately and engaged in guerrilla actions with a patrol of men. This was witnessed by Somalia's Chief of SM Colonel Luigi Dante Di Marco who, as an escaped convict, organised resistance in the Empire.

"During the period of his first escape - writes Colonel Di Marco in his proposal to award the Silver Medal for Military Valour to Palumbo - deployed in the Auia territory south of Harar, severely undermined, at the head of a handful of escapees and natives, the British military traffic between Giggiga and Hararof which the enemy himself later made chivalrous mention to me'.

Having fallen prisoner again, Palumbo did not give up and continued his series of escapes.

The most sensational and dramatic occurred in February 1942. Locked up in the Berbera prison in British Somalia, Palumbo wagered a golden pound with a British camp security sergeant claiming that he would escape despite the exceptional security measures.

And he was true to his word.

At night, after placing a dummy in his bed to deceive the sentries, with the help of other prisoners he managed to unhinge a window, lowered himself to the ground thanks to a rope made from the belts of his cellmates, evaded the vigilance of the British soldiers and in the dark ran towards the sea to reach one of our ships, moored offshore, sent to Somalia to evacuate, under British surveillance, the Italian women.

With a knife between his teeth to defend himself from the sharks that swarmed that stretch of sea, Palumbo jumped into the water and began to swim to freedom. Hours of inhuman fatigue, made three mournful by the strong wind blowing ashore; now at the point of exhaustion, unable to hold the knife between his teeth, he tucked it into the waistband of his shorts.

And it is to that trivial, forced change of position that General Palumbo owes his life.

"Exhausted from fatigue - tells - I was slowly sinking when, due to a sudden movement, the tip of the knife plunged into my buttock. The pain brought me to my senses: with a desperate effort I resumed swimming and, exhausted, I reached the Italian ship.

Seven hours spent fighting the adverse current had exhausted him, however, so that he was unable to grasp the rope that an Italian sailor had thrown to him, warning him to be quiet so as not to be seen by the English sentries on board the Vulcania.

"Pull me up with a two-stranded rope, I shouted to the sailors - Palumbo recounts - But my voice attracted the attention of a British sentry who appeared from the bridge and fired a shot in intimidation. He then pointed his rifle at the Italian sailors, forcing them to let go.

In anger and despair I regained my strength and swam back out to sea. Suddenly I heard gunshots behind me. I thought they wanted to kill me, instead they were just trying to make me give up my escape and get on board. Pulled up by the British by the arms, as soon as I set foot on the ship, I felt my strength run out and, in the Neapolitan dialect, I got a shock!

This made an English sailor who had helped me smile but I felt offended and pulled out my knife. To tell the truth, as I walked down from the command bridge to the sickbay, I saw my image reflected in a large mirror and I burst out laughing too!

In fact, I looked like an Indian on the warpath: all the scratches I had made in order to disentangle myself from the fences in the camp had become bruised and swollen, my hair was standing on end and I was impressively thin; in short, all in all I looked like a scarecrow!

As soon as he was refreshed, Palumbo was disembarked and taken back to the prison camp where the sergeant, with typical English fair play, paid the pound for the bet.

The episode is also mentioned, with considerable prominence, in the volume 'Lunga fuga verso il sud' (Long flight to the south) by Prince Giovanni Corsini, himself a protagonist of legendary escapes. At least a dozen books, however, refer to Palumbo's African exploits.

Another book, 'Africa without Sun' by F.G. Piccinni, details Palumbo's thirteenth and final escape, the one that finally brought him back to his homeland.

Reduced to a job as a smuggler of grappa, which he distilled clandestinely in the camp from which he escaped at night to sell it and thus obtain money for his escape, Palumbo often ended up in trouble. "The British colonel - is written on 'Africa without sunshine - Seeing him continually appear at the trial that was held for each offence, he finally told him that he was fed up with seeing him. Palumbo calmly replied to him: "Imagine me, Mr Colonel, having put up with you for over five years!"

So it was that the British colonel gave orders to put him on the queue of all repatriation lists.

But that one escaped from prison, reached Nairobi, then Mombasa, penetrated the harbour by climbing over the gate guarded by sentries at night, and went to a small island at the mouth of the harbour.

From here, when the first steamer loaded with prisoners came out, he swam towards the ship that picked him up and took him to Italy'.

With the end of the world conflict and a promotion for war merits, Captain Palumbo was assigned to the 1st Grenadier Regiment.

"At that time - tells - I came into contact with several parachutists, people who put on airs and graces, but really good people! So much so that I too decided to become a military parachutist: I turned to General Frattini and in 1948 I was able to take the course and finally obtain my licence'.

Just enough time to try his hand at his first jumps, then back on a mission to Somalia where he distinguished himself for his courage and decisiveness as the commander of Mogadisco recognised him:

'In the first half of April, Captain Palumbo performed an important mission in Migiurtinia for the recruitment of native soldiers, demonstrating calm and energetic behaviour in the face of unexpected difficulties that arose due to the hostile attitude of certain population groups. On this occasion I had the opportunity to see him personally at work in the Gallacaio area'.

Returning to Italy in '52 and promoted to major, he was finally assigned to the paratroop troops: "To be precise, at the Centro Militare Paracadutisti (later to become C.A.PAR) commanded by Col. Caforio - points out - It was a name I was not enthusiastic about; I protested, worked hard to get the old name of Military Parachute School and finally won thanks to the intervention of General Aloja, Chief of Staff of the Army'.

After a risky experience in Lebanon, Palumbo was given command of the Military Parachute School.

"At that very time - tells - three of my parachutists died from causes that were never ascertained, a mysterious epidemic that caused nationwide alarm and controversy. A journalist from 'Paese sera' took the liberty of writing that parachutists were taking excitants to make jumps.

Faced with this vulgar and cowardly insinuation, I reacted in a very decisive manner: I went, in plain clothes, accompanied by my wife, to the hotel in Pisa where the journalist was staying and, despite the fact that I had an arm in plaster due to a throwing accident, I slapped him in the face and sent him to hospital.

An episode that sparked violent controversy.

"But I also obtained widespread solidarity - General Palumbo is pleased - Do you know who defended me most vigorously? The Honourable Giulio Andreotti. "Free slap in a free state!" said the then Minister of Defence in one of his famous phrases. And in those days, the phrase "I'll give you a Palumbo!" was coined in political and ministerial palaces to indicate a particularly violent slap".

A few years later, another sensational episode, due to its political implications, brought General Palumbo to the forefront of national attention and controversy: he returned his decorations for military valour to President of the Republic Pertini in protest.

"I did so in protest against the awarding of the silver medal to Professor Bentivegna, the author of the Via Rasella attack that killed 33 South Tyrolean soldiers in German uniform and caused, in reaction, the killing of 330 Italians at the Fosse Ardeatine because the author of the attack did not present himself to the German authorities. Among the victims of the Fosse Ardeatine was also my wife's uncle, Air Division General Castaldi Martelli'.

Between one controversy and another, the then Colonel Palumbo gave heart and soul to his passions: parachuting and... wild animals.

In April '64, at the head of his paratroopers, Palumbo also set the military record for the simultaneous command-opening drop of 14 people from the axial door of the C-119.

"The launch, which I attended - tells - was conceived and planned by the Colonel Silver who took perfect care of their training.

That team was later nicknamed the cluster gang'.

His passion for ferocious animals, developed in Africa, continued in Tuscany, in a villa of friends where he bred tigers, lions, pumas and leopards.

Having abandoned the breeding of ferocious beasts (to the happiness of neighbours terrified by the not infrequent escapes of the animals!) the General is content with the company of less demanding dogs: like the famous Has Fidanken, protagonist - remember? - of not so distant television performances.

And with Has Fidanken well harnessed to his chest, General Palumbo often performed launches from four thousand metres, a happy and brilliant weekly commitment that helps turn his adventurous years into a perpetual youth.

First Bronze Medal for Military Valour

A daring fighter and ardent patriot, he marked every individual and department action with generous dedication, taking risks and pushing beyond all limits, spirit of sacrifice and high sense of duty. Commander of Dubat bands in a dangerous situation: for his unit he carried out risky actions with a few men and brilliantly carried them out by challenging and overcoming the danger. Constant example of disregard for danger and deep attachment to duty

East Africa May-June 1941

Second Bronze Medal for Military Valour

An officer of clear military virtues, he did not endure his imprisonment attracted by the overwhelming call of duty. After successive escapes in dramatic circumstances but failed due to the active vigilance of the prisoners, he managed, at great personal risk, to reach the sea and, after a long and perilous swim, to board a ship carrying compatriots with whom he returned to his homeland.

East Africa May 1942

Example of indomitable tenacity and persevering courage

General Palumbo left us on 9 February 2009at the age of 94. But we are sure that even in the next life, he will be feared and respected.

The plough leaves a furrow in the soil for sowing, there are men who leave an indelible furrow in their fellow men. Parachutist General Giuseppe Palumbo did this and more.

In 2007, at the age of 92, he declared the following:

"I order all paratroopers that at least once in their lives they go to the El Alamein memorial and do not forget those who fell for the Fatherland".

Rome, 27 October 2007, Parachutist General Giuseppe Palumbo

Paratroopers, orders must be obeyed.

a great Man.